ancestry & you: the design of belonging

the story of a dna test, an exploration of the ramifications of consumer genetic testing, and a study of how ancestry.com designed culture commodification

presented at ADX 2021

project originally submitted to anthropology + design

designing identity | graduate seminar @ the new school | 2020

by alexa mauzy-lewis

original header image by Janna Stam on unsplash

* disclaimer *

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals. I have tried to recreate events, locales, and conversations from my memories of them

Portions of this material are adapted from a forthcoming essay by the author:

“Between Water and Blood”

“it’s not just a matter of what you claim, but it’s a matter of who claims you.”

quote: Kim Tallbear | image: the author and her half-sister, rancho peñasquitos, circa early 2000’s“You know as soon as my Dad dies, I’ll stop having a reason to stay sober, like what's the point?” Tasha’s voice ricocheted out of my phone and around the four walls of my apartment. She took very few breaths in between her ramblings, pausing only for a drag of a cigarette.

“Do you mind if I smoke?” she asked.

“No, I’m not even there.” I laughed nervously.

“Oh, right,” she coughed back.

I heard a slow inhale, a light crackling. I could nearly smell her in my living room. These were the same sounds and smells that had always trailed my mother. Sitting on my flimsily-tiled floor, leaning against the broken futon, I tapped my fingernails against the coffee table. I glanced at the clock, counting the minutes of our call. She had been talking at me for almost two hours now, attempting to summarize a lifetime. I hadn’t said much, just a few obligatory “ahs” and “oh no’s.”

“So, what is your mom like, my sister, what is she like?” Tasha’s voice, raspy yet somehow still girlish, oozed excitement. I didn’t know what to say.

I looked up at my cat, his entire face smushed against the window, tail erect and twitching, watching a single sparrow idle around the patio. To his left was a photo of my dad and me at my high school graduation: his arm slung over my shoulder, both of us beaming with our identical noses. I realized I was letting too many moments pass without responding to Tasha’s question. But I wasn’t about to spill my heart out to this woman I didn’t know.

“I don’t know if her story is mine to tell,” I sighed.

***

For $99, Ancestry.com promises you “insights from your DNA, whether it’s your ethnicity or your family’s health.” With its “state-of-the-art” headquarters in Lehi, Utah, Ancestry® is the largest for-profit genealogy company in the world. Starting in the ’80s as a publishing company selling genealogy reference books, Ancestry later launched an online service for organizing family trees, and eventually entered the DNA testing market. Now, the company claims to have tested over 15 million people. Over the past decade, similar services have exploded onto the market. By 2019, more than 26 million people reported using an at-home DNA test.

By learning about their DNA, these companies promised clients would not only fill out their family trees; they'd acquire potentially life-saving information about heritable medical conditions. DNA was, for a moment, considered vital to the future of preventive medicine. When it launched in 2008, a similar company 23andMe boasted, “Genetics just got personal.” Consumers could decode the health risks written into their genetic makeup, seek personalized medicine, and maybe just find themselves along the way, by unlocking the rich histories of their bloodlines. The time between 2017 and 2019 saw the most rapid growth for companies of this vein.

This public infatuation with DNA testing swiftly peaked, then came to a halt. DNA testing turned out to provide very little useful or reliable medical information, and subscribers were left with not much more than a glorified social media network for their genes. In 2019, 23AndMe sold its rights to a foreign pharmaceutical company. Weeks later, the CEO announced massive layoffs. The DNA business at large was taking a tremendous hit. Privacy concerns were causing the sale of DNA tests to plummet. The general public was starting to think twice about what the DNA start-ups offering “direct-to-consumer” genetic tests could do with the incredibly valuable data of their genes. The risks seemed to outweigh any potential benefits.

The power of genetic databases was especially brought home with lurid clarity by a well-publicized criminal case. In 2018, the elusive murderer commonly known as the “Golden State Killer” was arrested. After 13 murders, 50 rapes, and 120 burglaries throughout the ‘70s and ’80s, he had eluded law enforcement for decades. By the time of his arrest, he appeared to be nothing more than a 70-year-old grandfather, intending on living out the rest of his life in his daughter’s house in California. Yet, using the service GEDmatch, law enforcement was able to track him down through scarce DNA traces to his fourth cousins. Police could use DNA databases to find you, even if you never submitted your own test. The infamy of the Golden State Killer could be a distraction for a dangerous precedent. Consumers began to wonder: how else can our DNA be sold and bought and used against us? Could tech companies market to us based on genetic tendencies? Could DNA be sold to third parties and influence insurance premiums and bank loans? Should these powerful tools really be at the disposal of law enforcement, or any company that wants to buy out the data?

As the public has become more skeptical of the medical benefits of DNA testing and the associated privacy risks, Ancestry.com has leaned back into its origins as a “family history” business, running campaigns around things like International Women’s Day, where they encourage consumers to “discover how your family story was shaped by defining moments in suffrage history.”

Ancestry has produced an abundance of commercials packed with celebrities finding long-lost siblings and uncovering their relations to dead presidents and civil war heroes. Their youtube channel includes original PBS programming called “Finding your Roots,” where public figures “uncover their fascinating family histories” with host Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The content can actually be quite beautiful. Queen Latifah cries when she is shown evidence that her ancestors were able to buy their freedom during legal slavery in the United State. Senator Bernie Sanders has a tender moment viewing the certificate of naturalization his father received after seeking refuge from the Holocaust. He also learns that the man who portrays him on Saturday Night Live, Larry David, is his distant cousin, and everyone has a good laugh about that.

Demand for at-home DNA tests has been on the rise again. Ancestry itself commissioned a survey showing that the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened interest in underlying health risks.

For the millions of us who had already rushed to turn our genetic makeup over to Silicon Valley in the name of self-discovery, sometimes more was revealed than proneness to diabetes, half percent French lineages, and, if we were lucky, trace blood-ties to dead presidents or war heroes.

In tandem with the boom of the DNA business, stories of nuclear families dissolving also flourished. DNA tests bring to light infidelities and lies that would otherwise have gone un-investigated. This information can unravel lives. Your father isn’t your father. Your mother has a secret family. Your third cousin is actually the Golden State Killer. As with DNA health diagnostics, there isn’t much guidance on what to do with your genetic information. Darker stories lurk in our DNA. Family secrets taken to graves, scorned lovers, lost children. The answers that were promised by DNA matching raised knottier questions about the nature of identity and family. You could use your body to try to predict its own failures, find out where it came from, and where it was going. But then, what do you do with this knowledge? And what do you do with the people revealed to you along the way?

***

“what a fuss for a name: famous or not, it's only a ribbon tied around a sack randomly filled with blood, flesh, words, shit, and petty thoughts.”

quote: Elena Ferrante, The Story of the Lost Child | image: deconstructed preview of the author's ancestry.com family treeIn 2016, my grandmother paid for an Ancestry.com test to arrive at my apartment in Brooklyn, unannounced. The kit arrived neatly packaged in a clean white box with subtle green and blue accent details. The Ancestry logo is a simple sideways leaf. The front of the box says, “DNA Activation Kit.” It includes a tube to spit in and mail back, as well as instructions for setting up your Ancestry.com account. It’s medical-looking enough to inspire some confidence.

Organizing the family tree was to be my grandmother’s hobby this year, and participation was mandatory. I rolled my eyes as I opened the box, thinking of her quest to confirm her icky obsession with a minuscule tie to the Sioux tribe. Grandma Catherine had adopted my mother, but I knew she already had the ethnic background of her daughter’s birth parents in hand.

There was a lot I didn’t know about my mother, but nothing a DNA test could tell me. My parents weren’t married when my mom found out she was pregnant. They had worked together when they were in their mid-twenties. Almost a decade later, they met again by chance. Their connection was brief. By the time she told him, my dad was already dating and soon to be engaged to my, now, stepmother. They all resolved to share me until I was seven. During this time, my mother’s prescribed back pain medication catalyzed into an opioid addiction, exacerbating the symptoms of her yet-to-be-diagnosed Bipolar disorder.

I don’t remember much about living with my mom. There are a few bright moments I can recall, like riding razor scooters together to school and eating T.V. dinners in front of cartoons. These are often overshadowed by memories of sleeping with an aching stomach after skipped meals, waiting alone, and plucking blades of grass from the familiar plot I parked myself in when she forgot to pick me up from school, murky half-memories of nights left alone with her boyfriend while she worked late. There was the day she did remember to pick me up from school but arrived without shoes on. That same night she broke her arm, inexplicably slamming it through a glass window in her bedroom. Hearing the shatter, the upstairs neighbors in our apartment complex called the cops. The officer on duty was my mom’s brother. He found me hiding under my bed. I don’t remember if he found me before or after the ambulance took her away on a stretcher. Actually, another officer might have come to the apartment, and Uncle Curt was just waiting at the police station they brought me to. My dad picked me up there at 4 a.m.

Following the overdose and a bitter custody battle, the details of which depend on who you ask, I permanently moved in with my dad and my stepmother, Dana. It was right before my eighth birthday. I was now their full-time child. After a year of often-missed court-permitted supervised visitations, I wouldn’t see my mother again for another ten years.

In my mother’s absence, Grandma Catherine was diligent about making sure I still felt connected to my non-biological maternal family. Without speaking more than a few words to each other, my father and my grandmother would take turns driving me back and forth between her house in Alpine, a town among the outskirt mesas in the Cuyamaca Mountains. From Poway it’s about a 45-minute drive, the wide four-lane interstate eventually spilling into a single-lane road, lined with never-ending curvy dry-brush brown mountains and repeating exit signs for small town after small town. When I make the drive now, the closer I get to Grandma’s, the more Trump 2020 bumper stickers I count on the road.

During one visit to my Grandma’s house, I went looking for my mom, a secret rescue mission. I sat in front of the relic home PC in a dark room lit only by the dusty screen. I typed in every combination of my mother’s first and last name I could think of and plugged them into various email address domains. I sent out close to a hundred copies of the same message from a freshly created Yahoo account, a plea somewhat reminiscent of lost pet posters stapled to telephone poles all across town. Some went unanswered, most came back to me, my heart falling at each RETURN TO SENDER notification.

Through my father’s and grandmother’s conflicting accounts of what happened, I tried to piece together my mother’s disappearance. Over these years, I would imagine my mother one day just showing up again, in the audience of my fourth-grade play or at my middle-school graduation. Until I didn’t.

Then, weeks before my eighteenth birthday and three months before I was set to move across the country, my grandmother picked me up to take me out to lunch. Before leaving my father’s driveway, she wordlessly handed me a letter written on five pages of torn yellow notepad paper.

Four years later, in my Brooklyn apartment co-occupied by roommates from Craigslist, I sat on a wobbly kitchen stool with the white "Ancestry DNA box in my hands, adorned with a simple green leaf logo and “Ancestry DNA” in intricate calligraphy.

I didn’t want to upset my grandmother and tell her how stupid I thought this was. We didn’t talk very much in those days. She unfriended me on Facebook for sharing too much of what she called “socialist propaganda.” My mom had graduated from sobriety camp and was now living in her house. We talked on the phone, once every few months, and updated each other on our lives. I would set aside an afternoon or two on my rare visits I went back to California. She had relapsed a few times, getting caught on some occasions, but not enough to be forced out of the program.

Our phone conversations were very stale, mostly an exchange of pleasantries and empty answers to “How are you?” We had walked on eggshells with each other from the last time I saw her in person, an incident we hadn’t talked about since.

I returned from the memory, turning the little box in my hands, the backside of the packaging promising me this is “where your story grows.” The note from Grandma Catherine urged that it might be proactive for us to be aware of any predispositions to health crises. I suspected this might be a way for her to try and reconnect the once-again severed ties between my mother and me. I spit into a tube to appease her and laughed.

***

Ancestry.com works almost like a dating profile, providing you with potential DNA matches to swipe through. After you submit your saliva and it is processed in a lab, you receive an email. The website generates a DNA story, with ethnicity estimates and an interactive map pointing to where your DNA traces appear across the globe. There is a page to build out a family tree (AncestryHealth nowadays can be accessed only with an extra fee).

Your DNA is then compared to other users’ profiles in the database. Ancestry uses a system they call a “match confidence.” Shared DNA doesn't always absolutely indicate relation. The score is based on the amount and location of DNA shared with another Ancestry.com user. DNA is measured in centimorgans. You have about 6800 centimorgans of DNA total. Depending on the number of common centimorgans between you and the other user, Ancestry lets you know the likelihood that you share an ancestor. Based on the amount, Ancestry can make a guess at the possible relationship. Siblings share 2,400—2,800 centimorgans of DNA. Parents and children share around 3,475. The number is the same between identical twins. You and your 5th cousin will share 6-20 centimorgans. After your DNA is processed, Ancestry will notify you of any potential matches on your profile and of the probable degree of relationship to them.

Ancestry DNA results take about 6-8 weeks after you drop your spit box in the mail. Catherine had been meticulously managing our profiles, updating her own tree, and crafting one for my mom. When the results finally came back, we spent a night on the phone saying, “Oh wow, how interesting,” to single-digit percentage matches in Portugal and France. We confirmed that my mother’s birth father was of Mexican descent, her mother Irish. My dad’s name automatically generated on my tree; his brother’s account popped up as a “likely relative.” His dead parents, whom I had never met, also appeared on my tree. I wouldn’t log into the website again until years later.

Then, in the summer of 2018, two years after we first mailed off our saliva, my mother’s account received a notification message. My mom had a biological sibling living in Encinitas, just half an hour away from Alpine, where she had spent most of her life.

Don worked in insurance. He was divorced, with two kids. He decided to make his dying mother a family tree, for her birthday. He took a DNA test to help. Until then, he had no idea he was adopted. Ancestry.com told him he had an “extremely high” match confidence score to a woman named Stasia Mauzy. The website suggested that she was his full biological sister.

My mom arranged to meet Don at the Broken Yolk Cafe, the same place she and I usually meet on the occasions I reluctantly returned to my hometown. It was equidistant from my dad’s house in Poway and Catherine’s home. Ordinary, middle ground, a tradition based on mere convenience. The kind of place where the menus read like novel manuscripts and the waitress probably went to high school with you. We would talk about things like the kinds of allergy medication I should try and engagement announcements, the rest staying mostly unsaid over a much too large omelet.

My biological grandparents had my mother when they were sixteen and unmarried. They gave her up for adoption. A year later, still unmarried, they had Don. They also gave him up for adoption. My mom told Don about how she had tried to find their real parents when she was younger. She had met her biological father once when she was pregnant with me. Her biological mother ignored her outreach. My mom liked Don right away. He was kind and funny. She didn’t have a car, and public transportation was non-existent in Alpine. She didn’t have a job and mostly stayed in my grandmother’s house all day. He would pick her up every few weeks and they would have lunch and talk about life. It was something she could do without my grandmother. For her, it was a happy revelation. She was close with her three adopted brothers, but I imagined she felt out of place sometimes as the rehabilitated black sheep. I used to be close with those uncles, but at some point, I think they also blocked me on Facebook.

I liked Don, too. I liked that he didn’t ask my mom questions about why she didn’t have a job or a car and took her out to lunch. I met him once with my mom, also at the Broken Yolk Cafe. He met us with his two kids, Luke, a son who was my age, and Sarah, a daughter who was 16.

My mom bragged to him about how I was getting ready to start my Master’s Degree. I was the first in our family to finish even a four-year degree. I smiled at her and kept to myself my thoughts on how she had nothing to do with that. Don was impressed with my job in public relations. I smiled at him and I kept to myself that the job was slowly sucking my soul out and I already had my two-week notice drafted. His daughter, my cousin now, told me about her water-polo team and how she had always wanted to go to New York. I told her she could visit me anytime. Don told us that his mother was not handling the news of us well. She had never wanted him to know that he was adopted, and he probably wouldn’t have ever found out without Ancestry. My mom asked the waitress to take a photo of all of us outside. With the outlet mall parking lot as a backdrop, we wrapped our arms around each other. My mom had the photo printed and mailed me a copy. She set it in a frame that said FAMILY in huge metallic font, tacky and swirly. I put it in a drawer. I haven’t seen Don or his children since.

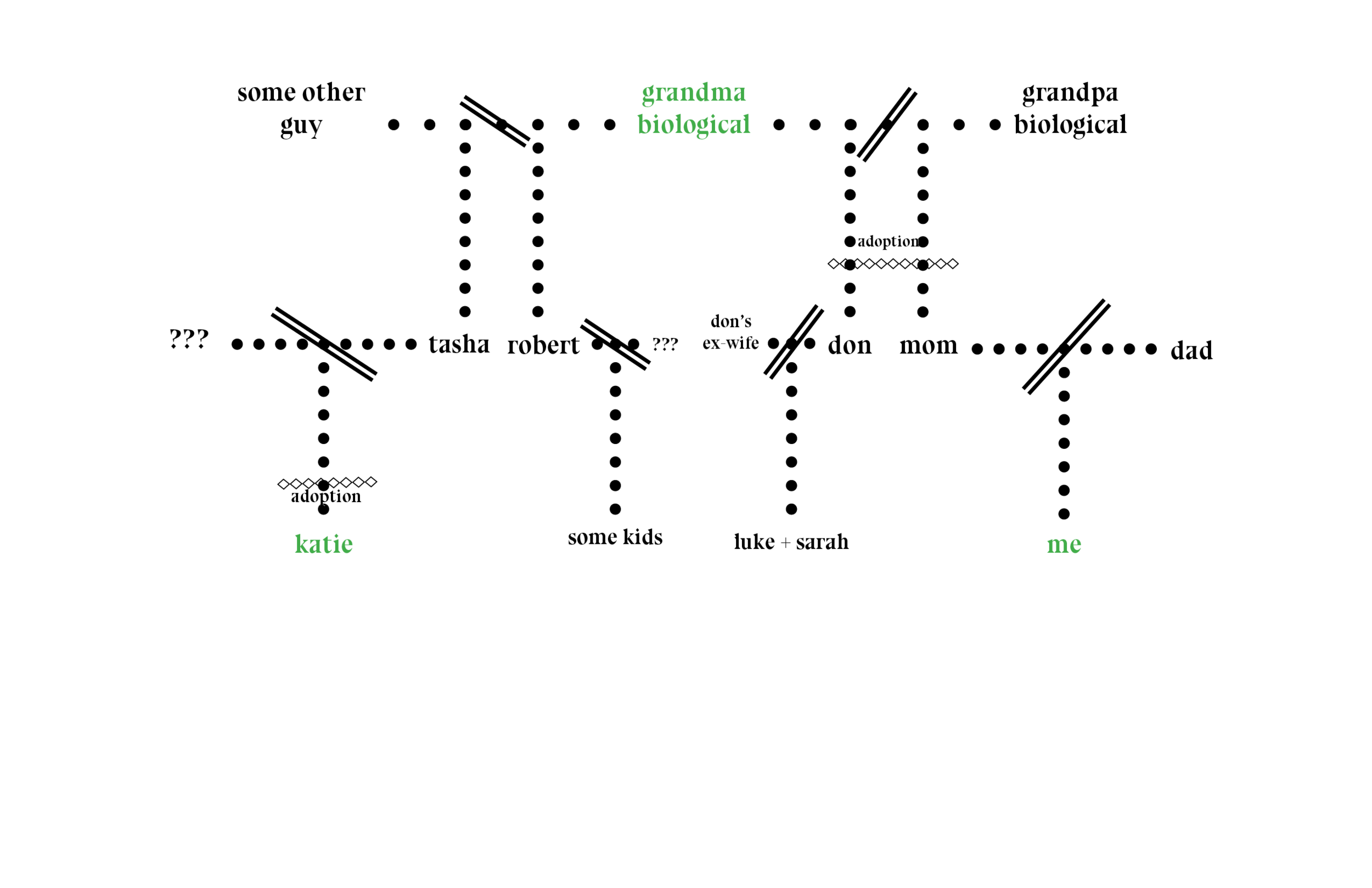

A few months after that meeting, my grandmother texted me that my mother’s account had received another notification. My mother and her new brother had two more half-siblings, Robert and Tasha.

After my mom called me with the news, I received a Facebook message request sent from Muncie, Indiana. Katie Canescos wants to send you a message: “Hey, this makes us cousins. I know this is really overwhelming but I am glad I found you guys.”

What happened over the next few years and what I have been trying to document and write down was a story filled with secret siblings, secret adoptions, shared drug addictions, shared traumas, and a newly sprouted tree of people I was related to, and who now wanted a relationship with me. I spiraled. These revelations in my blood, long lineages of addictions, and abandoned children, threw me into turmoil and an identity crisis. I started to write a book about my life before and after the DNA test.

In this project, which takes pieces from the beginnings of my thesis work and early attempts at writing to understand inherited trauma and internal struggle with ideas of nature versus nurture that defined my life, I turn my attention to taking a closer look at the product that gifted me my new relatives: Ancestry.

I started asking a series of questions. Why is our culture so obsessed with the idea of “where we come from?” What does that even mean and what should it mean? Should a stranger have access to you on the sole basis of sharing DNA with you? The complexities of lived experiences can’t always be organized into a cute little tree graphic. Why was this service designed this way and what will be the long-term failures and potential injustices of this design?

Ancestry and You: The Design of Belonging is an examination of consumer genetic testing and how the “design” of identity – as manifested through Ancestry.com’s testing kit, corporate branding, web resources, reports, and advertisements – masks the messiness and ambiguity of family ties and self-definition. Recounting my own fraught engagement with the service, this multimedia project mixes criticism and memoir.

***

“we tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

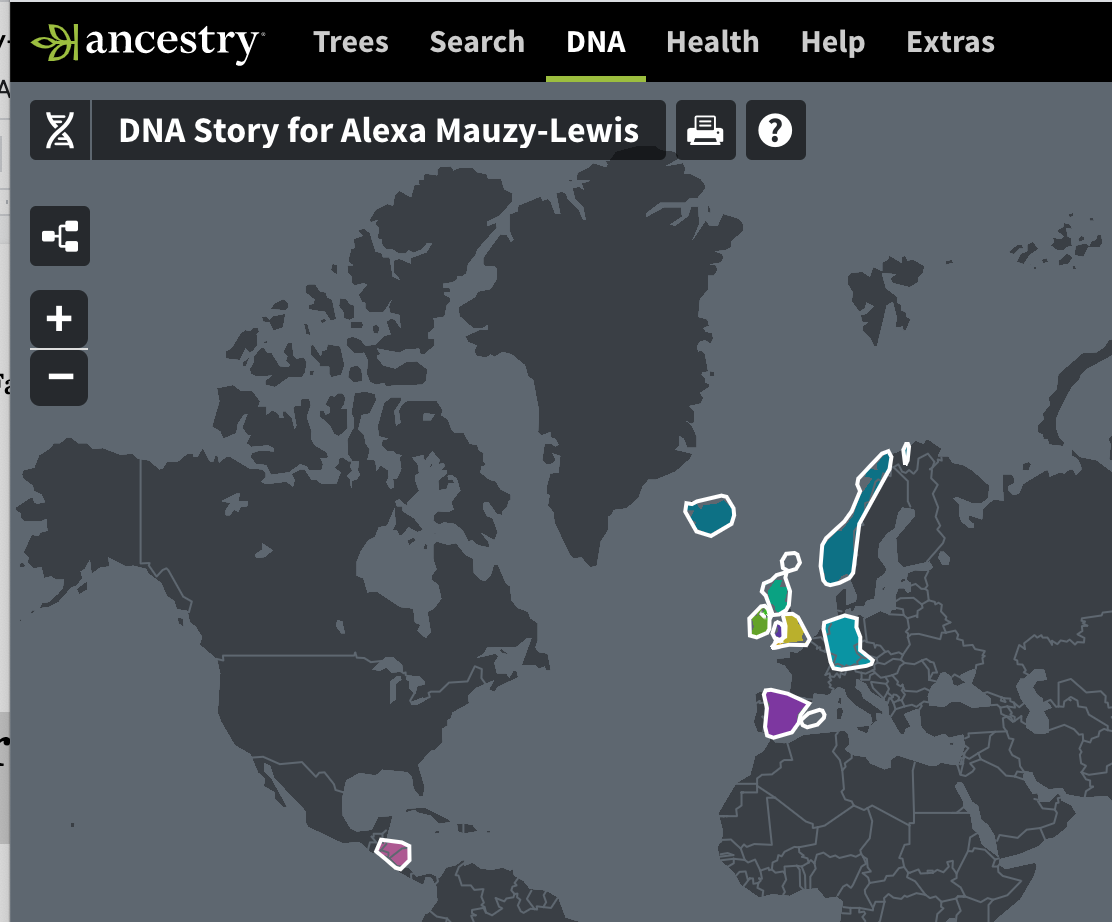

quote: Joan Didion | image: the author's mother, location unknown, date unknownWhen I decided to start writing this story down, it took me a long time to guess my password to log back into my account on the site, which was connected to a long-abandoned yahoo email address. Looking back at my profile now, I can click on a tab called “DNA” with a drop-down box to view my “DNA Results Story” and “Ethnicity Estimate.” My DNA story is a colorful map, areas highlighted where my DNA came from. If you click on an area it shares stories of the region’s history, contextualizing your genetics.

By chance, I met someone who worked as “a Context Curator” in the Editorial Department of Ancestry.com in 2012. They graciously spoke to me about their work and I will keep them anonymous.

“When I started out, there was a lot of experimenting going on. I worked on whatever was asked of me,” they told me. “The first thing I worked on was a massive timeline of ‘on-this-day historical’ factoids. It was boring. One for each day of the year. Once that was done, I worked on sample copy for a premium product where users could learn which celebrities they were related to. I remember drafting copy for Benjamin Franklin and Britney Spears. Not sure what came of that—if it was handed off to another team or if it was nixed. I imagined users would like that.”

“The main product I worked on was ‘Historical Insights.’ I think it’s still live,” they said. “The pitch was that it helped people understand the lives of their ancestors. Basically, the idea was we used records: immigration, birth, death, military, census, marriage, etc. to understand where people lived during important historical events. For example, say someone’s ancestor was living in Alabama in 1862. We would suggest they add a Historical Insight to their family tree that detailed the experience of living in the South during the Civil War. The product consisted of a short paragraph and a few images to give ‘the everyday man a sense of what his ancestor’s life was like.’ The phrase ‘everyday man’ was thrown around a lot. I don’t remember receiving more detailed info on the target audience, but I understood it mostly to be white retirees. Over the course of three years, I must have written hundreds of Historical Insights.”

“There were really uncomfortable moments working on some stories,” they continued. “How do I describe the experience of slavery in 50-75 words? How do I describe a massacre of Indigenous people? A pandemic? The Dust Bowl? The list went on and on. And keep in mind, you’re describing these events for presumed descendants of people who lived through these events. It had to be handled with care and thoughtful research. While I think that there was value in sharing short blurbs about American history with users who probably don’t know about it, for deeply serious topics, there needs to be context to do it justice. And there wasn’t space for a context in this product.”

When I asked about concerns around the use of DNA data, the context curator said, “The whole thing seems wrong to me, which is why I chose to not use the product, despite my coworkers saying how exciting it was. They added, “ I should mention my mom did, so I guess I’m in the system anyway. The most exciting thing she learned is that her ancient ancestors may have been French. She is convinced of that, but I’m not so sure. Also, who cares?”

In an essay adaption of her forthcoming book, The Lost Family: How DNA Testing is Upending Who We Are, Libby Copeland writes, “In the hundreds of interviews and conversations I’ve had with people who discovered something unexpected about themselves through a test, the overwhelming majority were grateful for that truth, even when the circumstances were painful, simply because they had the truth at last.”

***

Like my mom, Katie Cansecos knew she was adopted. She wanted to learn more about her biological identity. With the simple irreversible choice to spit in a tube and mail it off, she exposed a half-century-old secret. “Hello I’m adopted and I was wanting to find information. I’m related to the Pearson’s - moms side & Cansecos- dads side. Do you know any of them?” Ancestry suggested to her that my mom was her Aunt. This was almost right.

After my mother’s birth parents gave up their second child, Don, for adoption, my biological grandfather continued to refuse to marry my biological grandmother. She left him, got married to another man, had two more kids, Tasha and Robert. She never bothered her husband or her children with any information about her previous family.

After Katie found me on Facebook, we talked over the messenger app for hours. She had recently found her biological mother, Tasha. Tasha, like my mother, gave her child up after a lost battle with drug addiction. At age two, Katie was put into foster care. The same year I moved in with my Dad, Katie was adopted by a new family. She was just a year older than me. She, too, connected with her mother again when she was 18. Six years later, she decided to try and learn more about her father. She turned to Ancestry.com, and instead, she found me.

We couldn’t believe the parallels between our childhoods, sharing stories of our estranged parents and their respective addictions. Katie was now a social worker, helping children involved in the foster care system. She sent me pictures of her uncle and her grandmother. I realized this woman was my grandmother, too. The maternal line we both barely knew seemed to have a curse of losing children, of addiction, of mental illness.

Katie told me that Tasha was desperate to talk to my mom. She had always wanted a sister. My mom had not yet answered her calls. She wasn’t as thrilled to hear from Tasha as she had been with Don. They were both abandoned by the same parents. He was a comrade. Her two new half-siblings were only a few years younger than her and raised by the birth mom who never wanted to meet her. I wondered if she had carried that heartbreak for years, through unanswered letters.

My mother had no online presence to Google, so they turned to me. After I talked with Katie, her mother Tasha sent me a friend request, followed a few minutes later by her brother, Robert. Tasha messaged me “omg, hi. I cannot wait to speak with u guys im going crazy.”

Then Robert messaged me, not nearly as enthusiastic as his sister. “Hello im Robert. I understand we may be related. Nice to see you here.” His cover photo on his Facebook was of Trump standing in the Oval Office, caption “We Won.” He worked at an auto shop just up the street from where my mother was currently living. Unbelievably, Robert and Tasha grew up in Poway too. Poway, “The City in the Country," as it calls itself, the place where I had lived most of my life. The three of us went to the same middle school and high school, though decades apart. Tasha quickly asked for my number. Five minutes after I sent it to her, my phone rang.

On the phone, she told me about her life — a disturbing counterpart to the half-sister she never knew existed, stories of addictions and lost daughters and jail cells. It was similar to the line that ran between her daughter and me. I hadn’t gotten a single word in until she asked about my mother. It was hard to tell Tasha I didn’t know my mom that much better than she did. I gave the SparkNotes version of our story. She told me she loved me and was very excited to be my aunt. This left me a little terrified. She began to call me every other day.

A couple of months after our call, New Uncle Don reached out to me to tell me that Tasha had called him in the middle of the night, hinting to him that she was using again. I stopped answering her calls.

***

“ DNA testing is the messenger about truths long obscured.”

quote: Libby Copeland | image: pochoir print on canvas by the author titled "variations on my working mother."Ancestry.com tells me I have 636 4th cousins or closer in their system. When I click on the “Trees” tab, I see my dad, my mom, and me. You have the option to add building blocks to your tree. I once tried to build a more accurate tree for myself, using the service. It was nearly impossible. Adding in things like divorces, half-siblings, and stepparents was really complicated. I couldn't draw a line between myself and the people who actually raised me.

Because culture is not genetic. In 2018, the group Anthropology blog, anthro{dendum}, published a post titled “About those Ancestry dot com commercials” They describe an Ancestry advertisement that features a man named “Kyle.” Kyle begins the video stating, “Growing up we were German.” Kyle is wearing lederhosen and claims he belongs to a traditional german dance group. But then Kyle takes an Ancestry DNA test and learns he has zero German ancestors, and his DNA actually came from Scotland and Ireland. Kyle immediately buys a kilt. Kyle is Scottish now.

“Tracing your family genealogy can be fascinating,” anthro{dendum} elaborates. “That’s not the problem here. Kyle’s case is a perfect example of how misguided these tests can be. From an anthropological perspective, one of the primary issues is that these tests seriously conflate culture and biology...These tests paint an oversimplified, if not outright false picture of culture, history, genetics, and genealogy. There is no “Irish” or “German” gene or combination of genes. That’s just not how it works. Culture is shared, patterned, learned behavior.”

Ancestry’s marketing strategy to emphasize its ability to reveal proud cultural lineages and make “broken” families whole, paired with the presentation of results in the form of a map reifying a notion of genetic identity as geography, warps our ontologies of self. As anthro{dendum} further writes, "The take-home message is basically that these DNA tests tell you who you really are, despite your actual upbringing, cultural practices, family histories, and memories.”

*** explore ancestry commericals ***

Ancestry Commerical | Kyle

Ancestry Commerical | Sufragettes

Ancestry Commerical | Descendants of Honor

Ancestry Commerical | Queen Latifah

Kim Tallbear, an indigenous scholar based at the University of Alberta and author of Native American DNA, further writes, in response to an Ancestry.com ad featuring a woman “discovering” her Native American heritage, "We construct belonging and citizenship in ways that do not consider these genetic ancestry tests. So it's not just a matter of what you claim, but it's a matter of who claims you."

My spit says nothing about how I was raised and how I constructed belonging in my childhood. As I tried to expand my tree to add in my two half sisters, who I have lived with my entire childhood, I realized that the building blocks only give two gender options and an "unknown" option that it defaults to if you don't pick, which results in this gray amorphous person icon. (That is a lot to unpack on it’s own.)

Ancestry also can pull up public records related to your DNA matches and show you them, like a yearbook photo of my mother that popped up on my account. If someone matches DNA with you, you have the ability to contact them through the website, which leads to even more complications. What do you owe someone just because you share DNA with them?

Beyond the vast examples of interpersonal conflicts, there are a lot of serious cultural consequences of this database. Dr Sheldon Krimsky, Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University, gave a presentation on “Ancestry DNA Testing and Privacy” to American Medical Writers Association members at the New England Chapter meeting on September 24, 2018. Documented by Haifa Kassis, MD and Deborah A. Ferguson, PhD for AMWA Journal, they write, “It may not be clear to consumers that the contracts they sign to have their DNA sequenced for ancestry testing often include clauses that give away their rights to profits from any future products developed by using their genetic information.” They further elaborate that, “DNA sequencing data collected for ancestry analysis may also be requested by law enforcement agencies. Unless there is a court order, it is up to each company to decide whether it wishes to cooperate with law enforcement.”

The promises of DNA testing fall short, and the future ramifications can cause severe distress when you think about them for too long.

***

Conclusion

In the weeks after I decided to distance myself from her, Tasha sent me Facebook messages almost daily. Every “ding” sound notifying a new message from the app pierced my body with pangs of anxiety.

“Hi honey hope you are doing good.im up early my parole officer just came.anyway yr mom hasn't contacted me im worried she won't.i don't want u to say anything im just sad.I know it's hard on her.keep trying to tell myself that. Hows work? I still can't believe all this I have a niece and a sister I never have had how sweet .love u”

“Hi Alexa...hope u are doing good I have so much going on a little depressed but I will get over it.just wanted to say hi and I love u.my only niece.awe...never heard from yr mom I made all these plans to be her best friend oh well.you are beautiful my daughter is coming over for the weekend.i will have someone to hold lol.ttys”

“💖💖💖”

“Keep yr head up beautiful”

“Very much just going through some things ok I'm sorry”

I was torn between empathy and caution. She was reaching out to me for something. I didn’t know what it was. I felt paralyzed when I thought of responding. I didn’t want to be cruel. I also didn’t want to open myself up to her chaos when my family structure was already complicated enough. Was I obligated to have a relationship with these people because of our shared centigram count? I hardly knew how to navigate a relationship with my mother. Her genes didn’t raise me, but I still carried them.

My therapist once asked me, “What do you want from your mother?”

I didn’t know. Time and time again, she made it clear that I couldn’t trust her. But cutting her off completely didn’t feel right either. Now, we speak over text once every few months with an occasional phone call. She never responded to Tasha, but still meets up with Don now and then. Don was her brother now, but Tasha wasn’t her sister.

I, too, continued to ignore Tasha. Instead, I grew increasingly obsessed with the chain of lost children that has persisted throughout my maternal lineage and the addiction that has plagued both threads of my parentage. I meticulously researched Ancestry.dot com, read hundreds of their stories, even formed my graduate capstone project around investigating their services, how their family trees could warp our understandings of our own culture, our own selves. I talked about it so much that my grad school friends started to instinctively send me TikTok videos of dramatic DNA test reveals for my research. Ancestry gave me these new people in my life; what do I do with them now? I was thinking about my mother’s family, old and new, constantly. Yet, I couldn’t bring myself to call any of them.

When I first sat down to write about all of this, I called my Dad instead. I was beginning not to trust my own memories, and I needed grounding. I had always thought of him as a man of few words, not someone prone to talking about his own emotions. I realized that I also never asked him to. I tried to understand my past life with my mother, and images would rush to my head; I’d push them away. Were they memories or dreams or memories of dreams?

“Dad, was she sick when you met her?”

He shared details I had never heard before. How they met, what she was like when they were together. Their relationship was always very abstract to me. In my mind, my birth had been almost immaculate. I was not born out of any love or passion. I just came into existence between these two people who hated each other. I had never known them together.

My dad asked if I was writing about DNA because I was afraid I would inherit certain things from my mother. I told him I didn’t think so. Even though I was terrified it was true.

“You must have gotten more of my genes,” he said. “You and I are more pragmatic.” I laughed at him. He told me he was proud of our family, that my sisters and I stayed so close. “My brothers can’t separate me from our parents, and what they did to us. And I have all these half-nieces and nephews I’ll never know.”

“Maybe you should take a DNA test too, Dad.”

He guffawed at me. “No Lex, I am not giving Uncle Sam my DNA.”

I didn’t mention that, to some extent, he already had via his daughter’s saliva.

After we said goodbye on the phone, my dad texted me a few moments later. “The more I think about it the more interesting what you’re writing becomes. I think it would strike a chord with a lot of people.”

Despite all his flaws, my dad did his best to give his children a good life. Despite all her flaws, I wanted to believe my mom was still trying her hardest to get better. Katie just wanted to know where she came from. Tasha was looking for common ground, for love.

I, who had spent so many years trying to forge my own identity, was still looking for something to come home to, somewhere I could wholly belong. In a way, I could belong to all of them.

These DNA tests, with their growing list of flaws, have tried to capture something inherent in human nature. We look to other humans as anchors, grounding in the chaos. We tie ourselves to each other to establish a sense of place. These connections are created at random. Whether or not to keep them, is our own choice.

I texted my mom. “let’s talk on the phone soon. miss you.” I thought it could be one day at a time.

After that, I opened up Facebook.

“Hi, Tasha. I am sorry for not reaching back out sooner. Would you want to talk and catch up soon? Love, Alexa.”